|

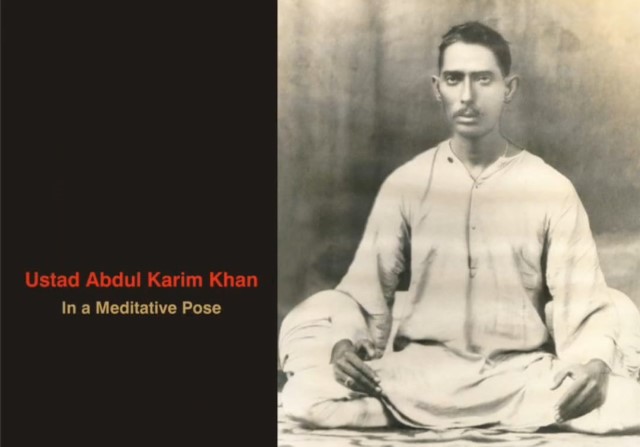

Abdul Karim Khan was born November 11, 1872 in the village of Kairana in western present-day Uttar Pradesh state in north-central India, a small agrarian town founded at the beginning of the 17th century. He was the eldest of four siblings, three sons and a daughter, each born about a year apart from one another. His family were part of a group of interrelated Sunni families in Kairana who revered the Chisti Order of Sufi saints, especially Moinuddin Chisti (b. ca. 1141; d. 1230), a Persian who traveled through Central Asia before settling in Ajmer, Rajastan, India. Abdul Karim and his brothers studied music as boys with their father, Kale Khan, and two of their uncles, who in turn had been taught father/uncle-to-son in a tradition traceable back to Ghazi Khan, Abdul Karim Khan's great-grandfather, and Ghazi's brother Ghulu Khan, who were employed as musicians in the court of Delhi at the beginning of the 17th century. The family's earlier musical lineage is thought to go back to either Dhondu Nayak, a Hindu musician who was known to have been active at Gwalior at the turn of the 16th century, or to a family of Sufi qawwali devotional singers and sarangi players who began as folk musicians and refined their music over generations.

During the 19th century, some exceptional musicians came from Kairana, the majority of them having been players of the bin (the predominant soloist’s string instrument before it was superseded by the sitar) and sarangi (vertical fiddle used to accompany vocalists), most notably Bande Ali Khan (b. 1829; d. July 7, 1895), who was said to have been the greatest bin player of his time, and to whom Abdul Karim Khan was related by marriage as well as in musical lineage. (Bande Ali was teacher to Hyder Bakhsh, one of Abdul Karim's primary teachers.) Bande Ali Khan had given both of his daughters in marriage to grandsons of Behram Khan (b. ca. 1727; d. ca. 1852), who in turn is believed to have been the son of a Hindu named Gopal Das Dagar who converted to Islam and who is now considered the seminal antecedent to the Dagar clan of vocalists and bin players. From the marriage of Bande Ali Khan's daughters and Behram Khan's grandsons Zakiruddin Khan (b. 1855; d. 1922) and Allebhande Khan (b. 1845; d. 1927), four great singers were born, their sons Mohinuddin, Aminuddin, Zahiruddin, and Fayazzuddin Dagar, who in turn trained their children as well, including the bin player Zia Mohuiddin Dagar (b. 1929; d. 1990), who then trained his son Bahauddin Khan (b. 1970), who continues that family's tradition in the present. Abdul Karim Khan had received early training on sarangi from his own family before and approaching Bande Ali Khan for lessons on bin. According to that family line, it was Bande Ali Khan who insisted that Abdul Karim Khan study voice, rather than bin.

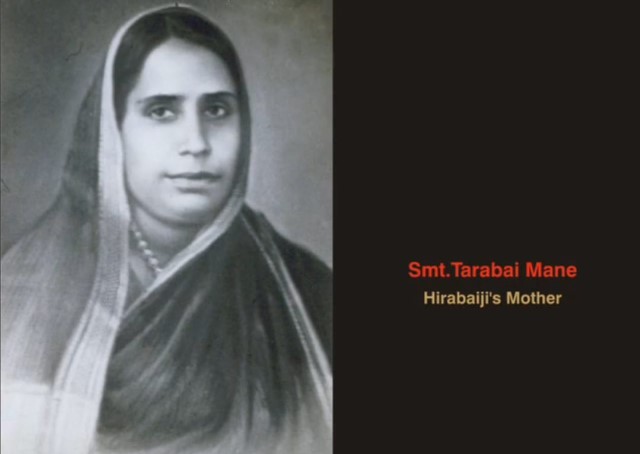

Abdul Karim Khan's Ancestral Home in Shamli, Uttar Pradesh As the Mughal Empire collapsed and the British East India Company accelerated expansion and control during the 19th century, the musicians of Kairana traveled to various courts, further than before and with increasing frequency. That there was a rail station only two miles from town - an easy walk, even with instruments and baggage - made it possible to take up paid residency in Darbhanga to the east, where Abdul Karim Khan's father and uncle were employed as singers for a while, or to Hyderabad, Indore, Jaipur and Mysore. By the age of 11, Abdul Karim and his brother Abdul Latif were being presented in concert near their home, and by 1888, when Abdul Karim was 16, his father took him to the court of Mysore to visit an uncle who was working there as a sarangi player. It was Abdul Karim's initial first-hand exposure to the "big time." For a classical musician of the 19th or early 20th century in Northern India, employment at a modest salary in one of the spectacular and opulent courts was a covetable way of life, and for a boy from a small village, the sheer scale and grandeur of the place must have been entrancing. In 1890, Abdul Karim Khan's father arranged for him to marry a cousin named Gafuran (b. 1873; d. 1973) and then to go out on tour to make his name. After periods at the courts of Kathiawar, Junagarh, Wadhwan, and Jaora, in 1894 Abdul Karim and his youngest brother Abdul Haque settled at the court of Baroda, employees of Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III of Baroda (b. 1863; d. 1939). The court of Baroda was an intellectual, political and artistic hotbed in the late 19th and early 20th century under its progressive ruler, who made substantial improvements to his domain's economy, educational system and infrastructure during the course of his six decade tenure. He outlawed polygamy, built hospitals, railways and irrigation systems, introduced compulsory free education, and built a still-functioning art school. His wealth was inestimable. A single carpet he owned, made from silk and deer hide and embroidered with glass, emeralds, rubies, and more than two thousand pearls, sold at Sotheby's in Qatar for five and a half million dollars in 2009, and a single diamond from his collection, the Star of the South, recently changed hands for nearly a half million dollars. He patronized, at various times, many of the greatest artists including the painter Raja Ravi Varma (b. 1848; d. 1906); poet, nationalist, Nobel laureate and author of the Indian and Bengladeshi national anthems Rabindranath Tagore (b. 1861; d. 1941); philosopher and freedom-fighter Sri Aurobindo (b. Aug. 15, 1872; d. Dec. 5, 1950) who worked at Baroda as a young man in administration at the end of the 19th century; and musicians Hazrat Inayat Khan (b. 1882; d. 1927), who later founded the International Sufi Order and performed as accompanist to Mata Hari in Paris, and Faiyaz Khan (b. ca. 1886; d. 1950), whose achievements as a singer were of similar scope and depth to Abdul Karim Khan's. (In one amusing account, the liberal and aesthetically-minded maharaja was convinced by his court musicians that music had the power to heal the sick, and so he installed a group to play in the palace infirmary. The response from the patients was an immediate demand for peace and quiet.) The intellectual atmosphere was one of rising nationalism and dissatisfaction with British control. In 1911, the maharajah was seen to publicly snub King George V when he arrived for a meeting in less than full regalia, bowed "extremely perfunctorily" and then, instead of backing away in obeisance as dictated by protocol, turned his back to walk away. The power and respect he commanded allowed him to continue rule despite this kind of affront to the crown. Among Abdul Karim Khan's duties as an employee of the court, apart from performing at the women's compound, the Lakshi Vilas Palace, and occasional concerts for the maharaja and the nobility, were work as a music teacher to the women and children. One of Sayaji Rao III's improvements to the court was the creation of a music school, the Gayan Shala, which was run by Maula Bakhsh. Abdul Karim Khan assisted Maula Bakhsh in his music theory work, and in particular on a project based on the novel idea of transcribing Indian music after the style of Western music. Abdul Karim, who was barely familiar with the rudiments of written Urdu, had help in transcription from a woman named Hirabai Mane, one of his music students and the wife of a nobleman. Her daughter, Tarabai Mane (b. 1879; d. 1946), also took an interest in the work. When Harabai died in the cholera epidemic in the first half of 1898, Tarabai took over her mother's work with Abdul Karim. Her father found coping with his grief for the loss of his wife overwhelming. He drank, got nasty and made accusations about Tarabai's relationship with Abdul Karim. Distraught by her father’s behavior and, legend has it, very much in love with Abdul Karim, she asked him to take her away. So, in 1898, four years after Abdul Karim Khan's arrival at Baroda, as his career and future seemed assured, the two eloped at night under cover of darkness along with Abdul Haque and a servant. They fled south to Bombay, where Abdul Karim knew an important personage in the theater business, who arranged for some paying concert appearances. Abdul Karim, who was still married to Gafuran, lived unmarried with Tarabai for a year. She was Hindu and noble-born; he was Muslim and poor. In 1901, he found work still further south in Miraj, where Abdul Karim contracted cholera. After Tarabai had nursed him back to health, they married, and the following year, 1902, their first son was born while they were on tour. Over the next fifteen years, they had a total of seven children, five of whom survived. During the first decade of the 20th century, Abdul Karim used Miraj has homebase, where he befriended the local instrument builders and learned about their craft, but he frequently travelled to perform at various courts and theaters, accompanied by Tarabai Mane and Abdul Haque. Over the course of the 20th century, economic conditions changed radically for classical musicians, and Abdul Karim was, less out of prescience than necessity, among the first to adapt. Previously, for centuries, classical musicians of stature were servants of the courts, patronized by and performing at the pleasure of highly refined connoisseurs of the arts. By touring constantly and charging admission, Abdul Karim Khan was heard by a wider social milieu, regardless of their ability to appreciate the details of the performance. In the smallest venues, he sometimes left a brass pot for collecting donations from the audience, and he was noted over the decades that followed for insisting that admission fees should be as low as possible so that concerts were often packed, and his reputation among the public-at-large grew. His shameful self-exile from the court of Baroda and the immediate need to support his family brought on the necessity for work, and he took what work was available, singing material that he believed in but that could also be appreciated by his audience. It was a new and democratizing way of presenting classical music that, decades later, after independence and the dissolution of the courts as artistic centers, became commonplace. By mid-century, most classical concerts were held far from the intimate evenings in music parlors where the music had evolved for centuries. Instead, huge festivals with hundreds or even thousands of auditors listened to through amplification to increasingly showy and immediately appealing sets by one performer after another. It was a devolution which mirrored another, a century earlier, which had set the stage for Abdul Karim Khan's own style. In the mid-19th century dhrupad, the austere, devotional classical music of Hindu India that had been the height of Indian music since about the 15th century, had deteriorated to its nadir into "screaming in the temples," according to Ustad Zia Fariduddin Dagar (b. 1932 and grandson of the aforementioned Bande Khan). Gradually replacing it since the 17th century was khyal (literally, "thought" or "imagination"), which retained dhrupad's ideals of dignity and precision but allowed for greater lightness and freedom, emphasizing the improvisatory Abdul Karim Khan in 1898 flights of the soloists. By the turn of the 20th century, dhrupad was all but dead, carried on by only a few families (most famously the Dagar clan), while khyal saw its golden age, embodied by great virtuosi including Abdul Karim Khan and his legendary contemporaries Alladiya Khan (b. 1855; d. 1946), Faiyaz Khan, and many others. Abdul Karim was instrumental in the expansion of the form. He was among the first and foremost classical singers to perform thumris, semi-erotic poems originally for the accompaniment of courtesan dancing girls, and other "light" styles that he encountered both at Baroda and in the musical theaters of his touring life, singing them with the same care in detail, nobility of spirit, and musical literacy as the more "serious" (masculine) forms. In February 1905, around the time their second child was born, he struck up a conversation at a music store in Bombay, where he wanted to order a pair of harmoniums. The owners of the store were also record dealers for the Gramophone and Typewriter company of London, and they arranged for him to be invited to record at sessions being held by the engineers William Sinkler Darby (b. Oct. 8, 1878, Orangeburg County, SC, US; d. Dec. 15, 1950, Baltimore, MD, US) and Max Hampe (b. Aug. 26, 1877, Genthin, Germany; d. Jan. 3, 1957, Berlin-Steglitz, Germany). They recorded him singing 32 performances (one of them never issued), each between one-and-a-half and three minutes long. The resulting one-sided discs were manufactured in Hanover, Germany and issued later in 1905, crediting the singer as "Prof. Abdul Kareem Khan, Baroda," probably listing the court under Abdul Karim's advice as his greatest claim to fame - a reasonable marketing strategy. He likely saw the discs as a potentially valuable piece of promotion for his larger concertizing and intellectual career, and, given the wide variety of musical work he was doing at the time to support his growing family, a paid gig of any kind was probably welcome. We can only speculate as to why he did not record again for almost three decades. Several factors suggest themselves, each of them a manifestations of pride. In 1905, when Abdul Karim Khan first recorded, the Gramophone Company (the first company to manufacture and market disc recordings, founded in Washington D.C. in 1892 and having opened its London office in 1899) had only been recording in India for about two-and-a-half years. When Abdul Karim Khan's voice was first bought and sold as part of the new technology of mechanical reproduction, his 31 performances were among five thousand recordings made in India during the period 1902-08. The limitation of the medium itself both in sound quality and duration discouraged many of the best musicians from commodifying their art into records. For an improvisor capable of singing a single composition for an hour at a time like Abdul Karim Khan, the format's demand that a performer demonstrate his art in a couple of minutes was anomalous at best and insulting at worst. Meanwhile, there was little status to be gained from having recorded. Phonographs were expensive at first and only available to wealthy households or prosperous businesses, but over the course of several decades, record players and the discs to play on them became increasingly affordable, and whatever social cachet might have been hoped for by owners of "talking machines" (and, by extension, recording artists) dwindled. Like many of his contemporaries in the arts, Abdul Karim Khan was keenly aware of the politics of the British in India. In the mid-20s, he performed benefit concerts for Gandhi's non-violent resistance movement. Although there were small independent record companies in India during the 10s and 20s, the Gramophone Company (renamed in 1916 HMV, His Master's Voice) dominated the marketplace, towering over the competition and ultimately devouring each independent like an elephant eats peanuts. The Gramophone Company set up a record pressing plant in India in 1908, and it remained the only manufacturing facility on the subcontinent (where the vast majority of the shellac used in the worldwide manufacture of 78 rpm discs was harvested and processed) until 1969 - a near-monopoly on one of the largest markets on earth for more than 60s years. In a sense, not to record was its own passive resistance against a British financial and media behemoth. A further reason for some of the best performer's of Abdul Karim Khan's generation not to have recorded is more subtle. In the tradition of guru-to-disciple transmission of classical music in India, the performer himself is a living manifestation of his art's history, and each performance is potentially decisive. The intellectual and aesthetic discipline, not only of the individual, but of perhaps centuries of of his handed-down lineage may be, on one hand, called into question, scrutinized, or debunked, or, on the another, accepted, understood, and taken within the hearts and minds of individuals in the audience. In performance, a singer or instrumentalist, with lifetimes of knowledge and refinement at his disposal has the opportunity to claim the moment, demonstrating not just his own worth but that of his entire lineage. Competition among musicians, not simply for rank and employment, but for whose aesthetics will extend through time matters deeply to the long-view understanding of the meaning of performance. From a Western understanding now, recording are seen as an ideal vehicle for long-term transmission of ideals and aesthetics, but during the 10s and 20s in India, recordings may have been seen by classical musicians as cheap novelties which could only interrupt the listener's enjoyment with their acoustical imperfections, mechanized trappings and utter lack of corporeality. The Western classical elite largely viewed records as outright chintzy until the signing of Enrico Caruso for the modern equivalent of of about $15,000 to record ten songs on April 11, 1902. During the first decades of recording in India, any musician, even at Abdul Karim Khan's level artistry, would have been paid a disrespectfully tiny fraction of their European counterparts, so it's not surprising that respected musicians neglected or refused to perform for the machine. From 1908-1910, Abdul Karim Khan, Tarabai Mane and their family lived in Sholapur and then relocated still further south to Pune, where, with funds from friends and local dignitaries, they founded a music school on the ground floor of their three-story home. They began in 1911 with eight students, one of whom was one of Abdul Karim's sons and two of whom were financial parters in the school, but through promotional advocacy of friends, by the end of the following year, they had 50 students. At the same time, he began to publish short books of musical transcriptions and theory, derived from his earlier work at Baroda. The school ran mostly in the red financially, even as Abdul Karim toured with mounting success and attended conferences where his theoretical work was, if not accepted, at least taken seriously. He wished his students to stay with him for eight years, but they mostly left after a few years, mostly going off to sing in theater companies or to teachers who would show them more constant attention. Abdul Karim was constantly taking leave to tour.

Abdul Karim Khan's wife - Smt.Tarabai Mane Even as his career came into full flower publicly in the late 10s through touring and publishing, his relationship with Tarabai showed signs of wear. She ran the schools while he was so often away, and at the same time, she raised their increasing brood of small children. Abdul Karim adored the children and presented the boys in concert between the ages of 3 and 5. But the couple quarreled over the Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan at All India Radio children. Abdul Karim insisted on a proper Muslim upbringing and made his wishes emphatically clear that if the children wished to have careers outside of music, they should follow those other paths. Tarabai, burdened with managing Abdul Karim's career while schooling their children, felt that the children, the boys in particular, should follow in their father's footsteps as musicians, if possible. Tarabai was assisted by Abdul Karim's cousin Abdul Wahid Khan (b. ca. 1882; d. 1945), who moved to Pune and taught at Abdul Karim's school around 1913. Abdul Wahid had also been a long-time student of Abdul Karim's guru at Baroda, Hyder Bakhsh. Abdul Wahid and Abdul Karim were equals as artists, but had a complicated relationship. The differences between them were physical, temperamental and philosophical. Abdul Karim was slender to the point of gauntness; Abdul Wahid was corpulent. Abdul Karim was married to a Hindu, taught Hindu students and operated in a largely Hindu sphere of intellectuals; Abdul Wahid was a devoted Sufi who felt that Muslims offered too much to Hindus and received too little in return. Abdul Wahid was also married to the sister of Abdul Karim's first wife - the one he had abandoned in fleeing Baroda. Abdul Wahid traveled little and, as a performer, insistent on as much time as possible to carry out his incredibly long expositions of raga. He was also a serious opium-smoker, who was in later years nicknamed "the deaf" because he had damaged his hearing in the stoned practice of playing high, steady drones for long periods on the upper register of the sarangi. (Accounts exist of Abdul Karim Khan's use of opium, but others deny this.) During his time at Pune, Abdul Wahid often acted as intermediary between Tarabai and Abdul Karim, in addition to teaching many of Abdul Karim's students, and Abdul Wahid is known to have accompanied Abdul Karim onstage. As Abdul Karim and Tarabai fought increasingly over the raising of the children and the management of the school, she also suspected him of infidelity. He did hide lessons to female students from her, but whether it was due to infidelity or avoiding the mere suspicion of it, we'll never know. In 1922, after 22 years of marriage, Tarabai had had enough. While we was on tour, she simply left, taking their five children, aged eight to eighteen. They previously had both Muslim and Hindu names, but their mother from that point forward used only their Hindu names. Abdul Karim was 49 years old when he learned by telegram that he had lost his family. He returned home, despondent, enraged, and feeling betrayed and slandered by his ex-wife. And to make matters worse, his mother Jilaye showed up to plead with Abdul Karim to reunite with his first wife Gafuran, who had been waiting for him loyally to return for more than two decades while living with her family. (Jilaye had brought Gafuran to Abdul Karim in the same hope nine years earlier in 1913.) Abdul Karim would have none of it. He responded to his pain as many professional musicians might. He went back on tour. He took with him two disciples, sisters, one of whom, Banubi Latkar (b. 1905; d. 1970) was the same age as his eldest daughter. Banubi became his companion and then, in 1929, his wife. For several years, his concerts took on the quality of a vaudeville act, featuring performances by his sisterdisciples on sitar and jalatharangam (melodic-percussive ceramic cups), virtuoso triple-tabla performances, and, incredibly, performances by Abdul Karim's hound, who he announced to the audience as "Ustad Tipu" and who would howl along with Abdul Karim's singing. "A Wonder of Age," announced a newspaper ad of March 1922, "A big hound will exhibit its skill to follow a songster in his tunes. A Marvelous Art." If only there had been recordings made. If he was singing with his dog and cracking up a little, such is the life of a man who has seen hard times. Three of his estranged children, meanwhile, studied under his cousin Abdul Wahid Khan, likely straining the relationship between the cousins, and came into their own as performers in musical theater, film and on record. Whether his second wife's departure and the loss of his children marked a change in his style, making it more contemplative and inward, as some have said, or if his genius only came into full flower in his 40s, as others have remarked, is difficult to judge. Most of the 1905 recordings available are of such poor sound quality and so brief Ustad Tipu that all that we receive for sure is that as a young man, his voice was incredibly elastic, like mercury pouring through a textured terrain of notes, and that he was given to heroic, almost macho, displays of virtuosity (well suited to the brief duration of the discs). He recorded again in 1911 or 1912 for the French Pathé company, and some recordings were issued on vertical-cut discs (a format requiring a different playback system than standard lateral-cut discs), but no copies of these are known to exist. In 1932, he began to be convinced that recording would be a good idea, partially because his respected contemporary Ramakrishna Vaze (b. 1871; d. 1945) had recorded. That year he recorded four performances for the independent, Indian-owned Megaphone label. Again, no copies of those recordings, not even their titles, are known to exist. In 1933, he began negotiations with the German-owned Odeon Record Company, ultimately resulting in a contract for six sides that were made for a new Odeon subsidiary based in Bombay. All of those performances are presented on this LP. The recordings of the 30s display every bit of the virtuosity of the 1905 records, sounding quite like the same young man, but his voice had taken on a noticeably feathery and exceptionally honied quality. He pushed the sound from his solar plexus, yes, but he rarely allowed you to hear him do it, floating tones like petals across the surface of the song's stream. Other changes to his music might be accounted for by combination of the mellowing of age and the ever-expanding horizons of his study and musical consideration. It's hard to say for sure. The Odeon performances present the distilled essence of his art. The introductory improvisations, which would have lasted much longer in concert, have been shortened to a matter of seconds. The records feel carefully planned and considered to give maximum clarity and affect in the brief fourminute window of the side of a 12" 78 rpm disc. Contemporary recordings of Abdul Karim Khan's peers, even great ones, often end abruptly or carry little formal structure. They often simply begin, contain several minutes of singing, whatever section from a longer piece, and then end unceremoniously. Abdul Karim Khan's records, in contrast, often demonstrate care for the creation of a feeling of complete performances, full of drama and the relief of suspense - micro-universes of feeling, despite their brevity. A little less than a year later, he recorded again for Odeon (which had been in the process of merging with HMV in the early 30s but remained separate during the rise of the Nazi party during the mid-30s), and over the next ten months waxed another twenty-five recordings, apparently convinced of the merits of recording. (Pieces from these sessions comprise the remaining four performances on this LP.) Two of the performances were made in the Canarese language of southwestern Karnataka state at the request of the maharajah of Mysore, a faithful patron for two decades. In December of 1936, he recorded eight more performances, two of them as an instrumentalist playing the bin as a tribute to Kairana's Bande Ali Khan. In October, 1937 Abdul Karim Khan had performed well-received concerts in Madras. He had received an invitation from the poet, philosopher and nationalist Sri Aurobindo (b. 1872; d. 1950) to perform at his ashram in Pondicherry in the southeast of India. On the train journey to Pondicherry, he felt unwell and decided to detrain to rest on a railway platform. According to one story, he laid down on a bench, sang a prayer in rag darbari and passed away. In another story, he turned to the man sitting next to him and told him, "I'm going now," pulled down his turban and died. It was October 27; he was 65 years old. The cause was heart failure. Radio stations across India interrupted their programs to broadcast the news of his death. A crowd assembled at the train station in Miraj when he casket arrived a week later.

Abdul Karim Khan's Samadhi Tarabai and the five children had all remained in the music business. One son withdrew from singing publicly in the early 20s but worked with his mother in the management of the others' careers before going into the hosiery business. One daughter stopped performing in the late 30s after her marriage to focus on her domestic life. The others performed and recorded into the late 40s. Suresh Babu Mane recorded periodically for about twenty years and appeared in a number of films, but in middle age became fascinated with alchemy, which he hoped would be the solution to his persistent domestic and financial difficulties. The toxic byproducts of his experiments ended his life at the age of 51. It was Tarabai and Abdul Karim's first daughter, Hirabai Barodekar, who was the greatest musical success of the family, a true star of stage, screen and record, who was one of the most important voices of her era and one of the most celebrated female singers of Hindustani music. Among her numerous honors, she was awarded the second-highest civilian title in India, the Padma Bhushan and the highest award for performing artists, the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award. On the day of India's independence from the United Kingdom, she was selected to sing the national anthem publically in the nation's capital. She toured China and East Africa as part of a national delegation in 1954. She died November 20th, 1989, age 84. Having opened a music school of her own in the early 20s, launching her children's careers and becoming a beloved grandmother, Tarabai Mane died nine years after Abdul Karim Khan, October 20, 1946, in Pune. Abdul Karim Khan's first wife Gafuran remained faithful to him, never remarrying; she died at the age of 101. His third wife, Banubi Latkar, recorded six songs at his December, 1936 session, four of which were released by Odeon. She continued to teach a few students for a short period after his death, but in her grief she became a virtual recluse, retiring to a private life with her brother's family and participating little in the various memorials for her late husband. Despite having been born Hindu, when she died, February 16, 1970, she was given a Muslim burial next to Abdul Karim Khan. In 1946 the English HMV company acquired the Ruby record company. The following year, as India declared independence from the United Kingdom, HMV took custodianship of the remains of the Odeon label. (Its Berlin plant was ransacked and mostly destroyed by the Russian army in 1945. Paul Vernon reports that the company's paperwork was incinerated in the courtyard and that "metalwork and shellac file copies were apparently used for target practice and large areas of the complex were set on fire.") HMV began to reissue Abdul Karim Khan's Odeon sides on the Columbia label in India in short order, inspiring innumerable singers who began their careers by imitating his recorded performances. Among the earliest of them was the great Bhimsen Joshi (b. 1922; d. 2011) of Karnataka state who, after hearing Abdul Karim Khan's "Piya bin nahi avat chain" (included on this record) left home as a teenager to learn music, ultimately training with Abdul Karim Khan's disciple Sawai Gandharva (b. 1866; d. 1952) and Abdul Wahid Khan and becoming arguably the greatest vocalist of the the mid- and late-20th century of the Kirana school and certainly one of the greatest of India, generally. In 2008, he was awarded India's highest civilian honor, the Bharat Ratna. He, and many of the other singers who carried on the regal ebullience and deep pathos of Abdul Karim Khan for the rest of the century had been students of Abdul Wahid Khan, who made no gramophone recordings himself. Only two LPs have been released of recordings of Abdul Wahid's performances for All India Radio. Ustad Abdul Karim Khan's 10 day association with Shri Sai Baba: It was customary for any musician, singer or any talented person to present themselves in Baba’s durbar. Baba loved music and had a great deal of knowledge of it. Khan Sahib Abdul Kareem Khan was one such talented singer. He had graduated in Hindustani Classical Music from the Kirana Gharana. This gifted singer had a voice that tinkled like a bell, besides being a wise man. His name and fame had spread far and wide. In 1914, Khan Sahib Abdul Kareem Khan had a programme in Amalnere, where he was invited by Pratap Shet. There Shri Bapu Saheb Buti and various other devotees attended his programme and invited him to Shirdi. Khan Sahib cancelled the rest of his programme to visit Shirdi. He had a great respect for saints and he felt this was a good opportunity to pay homage to Baba. He and his entourage of students and musicians arrived in Shirdi. They camped in the hall of Tatya Kote Patil’s house. In the evening when the usual bhajans took place in the Dwarakmai, Khan Sahib was sitting alongside the singers. Then Khan Sahib went for Baba’s darshan. Baba blessed him and made inquiries about him. Then Baba asked him to sing a Tukaram Abhang in Marathi. Thus Khan Sahib in a melodious voice sang the below Abhang: Abhang: hechi daan dega dewa goon gaien aawadi nalage mukti aani sampada tuka mahne garbhwasi Meaning: O God, grant only this boon. I may never forget Thee; and I shall prize it dearly. I desire neither salvation nor riches nor prosperity; give me always company of the good. Tuka says: On that condition Thou mayest send me to the earth again and again.

Baba liked this Abhang in Raag Piloo so much that he closed his eyes and heard it attentively. Then Baba said “You ask for a boon in such a way that one cannot but give it to you. Now don’t make haste to leave Shirdi. Do not worry about your family, everything will be all right.” Then turning to Tatya Kote Patil, Baba said, “Give them Shirdi’s Badashai treatment.” The next day Khan Sahib received a telegram from his wife Tarabai that his daughter Gulabkali was seriously sick and he should return home. Khan Sahib brought the telegram and handed it to Baba. Baba reassured him and asked him to bring his family to Shirdi. His wife and daughter, came to Shirdi. Khan Sahib carried his daughter, who was hoovering at death’s door, and laid her on Baba’s feet.

Abdul Karim Khan's Wife Tarabai

Abdul Karim Khan and his wife Tarabai Baba took some ash from his chillum and mixed it with jaggery. Baba made a mixuture of it with water, and gave it to her to drink. After two days of this treatment, Gulabkali was on her feet. Baba kept Khan Sahib and his family in Shirdi for 10 days. Meanwhile Khan Sahib asked the other devotees “What are the bhajans that Baba likes? Then he learned them by heart and practiced them, thus he was ready to present them before Baba. The entourage of singers, students and musicians consisted of about 20 people. Tarabai asked Mrs.Kote Patil if she could do the cooking and houshold chores. Mrs.Patil replied “What you say is right, but I have orders from Baba to look after your comforts. You can however tell me what you would like to eat. And how you would like to eat and I shall prepare in the same way.” That night Tarabai sang some bhajans and ended with Gaalina Lotangana and Baba was very happy. Khan Sahib was concerned about his music school at Poona, and Baba reassured him. Baba then gave him permission to leave Shirdi saying “You are eager to go, but do not return to Poona. Go to Varahad, as the cotton trees are in full bloom.” Then Khan Sahib sang some of the Baba’s favourite bhajans and that baba particularly liked which were: Abhang: je ka ranjale gangale tochi sadhu olkhawa mrudu sbahya navneet jyasi apangita pahi daya karane je putrasi tuka mahne sango kiti Meaning: Know him to be a true man who takes to his bosom those who are in distress. Know that God resides in the heart of such a one. His heart is saturated with gentleness through and through. He receives as his only those who are forsaken. He bestows on his man servants and maid servants the same affection he shows to his children. Tukaram says: What need is there to describe him further? He is the very incarnation of divinity.

Abdul Karim Khan Sahib sang another Baba's favourite Kabir Dohe "Is Tan Dhan Ki Kaun Badayi, Dekhate Naino Mein Mitti Milayi". Khan Sahib also sang a bhajan titled “Jogiya”. Baba blessed him and stroked his back and gave him a silver coin, saying, “Do not spend this coin, keep it in your pocket at all times.” Then he gave 5 rupees to Tarabai and asked her to keep it in her trunk. Baba took a lot of Pedas and put it in her ooti. “Filling the ooti” is a wonderful tradition, especially in Maharashtra, where the elderly or the guru blesses an fills the ooti. Women usually keep their heads covered as a sign of respect. The lady gathers up that part of her sari that diagonally covers the abdomen and places both ther hands beneath that part of the sari when she receives the blessing (i.e., coconut or whatever the guru may give). Here Sai Baba put a large number of Pedas in her ooti. (Source: Baba’s Vaani by Vinny Chitluri and Shri.Nagaraj Anvekar, Bangalore. Picture Courtesy: Shri.Jignesh C.Rajput, Surat & Shri.Pranav, Telangana) |